One of the world’s largest swamps in Western New Guinea is home to an ancient ethnic group, the Asmat. Surrounded by rich vegetation and many rivers, the Asmat are known for their impressive carvings and accompanying rituals. Each wooden creation tells a story of their rich culture and profound connection to nature. Perhaps the most outstanding manifestation of Asmat art are the imposing bisj poles. These intriguing wooden monuments serve not only as masterpieces of craftsmanship, but also as symbols of the spiritual connection to their ancestors and the power of the supernatural. What exactly do bisj poles symbolize, how are they made and what do you see depicted in them? We wrote a brief description of these fascinating carvings.

Nine Bis Poles, from left to right: Jiem (artist), Otsjanep village, c. 1960; Jiem (artist), Otsjanep village, c. 1960; Terepos (artist), Omadesep village, c. 1960; Jewer (artist), Omadesep village, c. 1960; Fanipdas (artist), Omadesep village, c. 1960; artist unknown, probably Per village, c. 1960; artist unknown, Omadesep village, late 1950s; Ajowmien (artist), Omadesep village, c. 1960; Bifarq (artist), Otsjanep village, c. 1960, Asmat people, Faretsj River region, Papua Province, Irian Jaya, Indonesia, wood, paint, fiber (Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

What do you see?

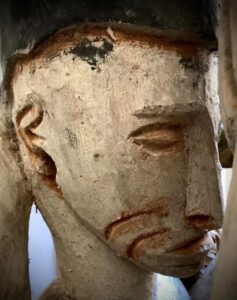

Bisj poles are carvings several meters high. They often have light colors and are usually painted with white lime and red ochre. A flag-shaped protrusion can be seen at the top of the pole. The pole consists of several human figures placed on top of each other. Sometimes the human figures are placed upright and – in some cases – backwards or upside down. The protrusion at the top represents the phallus, this part is also called tsjémen. It often contains smaller human figures and uses repeated motifs. The open style of carving is also called ajour.

How are they made?

Bisj poles are made by the Asmat people. The Asmat are well-known woodcarvers in the Pacific region. Woodcarving for ceremonies and rituals is considered an honorable task among the Asmat. It is performed by so-called wow-ipits, master woodcarvers.[1] The bisj poles are made from mangrove trees such as wild nutmeg trees.[2] The projections at the top are the plank roots of the tree. So, basically, it is the trunk of the tree upside down.

What is the meaning behind the bisj poles?

Asmat also means wood people. In the origin myth of the Asmat, people were created from wood, which emphasizes the deep connection to nature and the spiritual in their cultural identity.[3] In this fascinating origin myth, the creator Fumeripitsj brought to life a wooden figure.[4] After this figure was brought to life, he chopped himself into pieces and from each piece a human being was created.

The Asmat honor their ancestors every year during the bisj festival. The bisj festival is an elaborate ritual that can last from weeks to months. During such a festival, there is singing and dancing, and various ceremonies take place. Central to this is the carving of the bisj pole, which is also known as an ancestor pole or spirit pole.[5] The human figures represent the individuals in their community who died that year. The word bisj is derived from mbi, meaning spirit or phantom of the dead. The completion of the poles marks the end of the festival.

The bisj poles made during the festival are meant to honor and commemorate the spirits of deceased family members. The poles serve as a connection between the living and the dead. The ritual festival is also meant to ensure that the dead can travel to the afterlife (Safan) so that their spirits do not continue to roam the earth.

In the traditional worldview of the Asmat, there is a balance between life and death. By celebrating the dead, they would also welcome new life. This is called the continuity principle. This philosophy around life force plays a major role in the worldview of the Asmat.[6] The phallus at the top of the pole symbolizes fertility and the hope of new life to restore balance. It also symbolizes fertility in terms of nourishment. This is also reflected practically in that after the last night of the bisj festival, the Asmat leave the poles in the sago palm groves, where they decay and create a supernatural feeding ground.[7] The sago palm groves are the main source of food for the Asmat.

The two bisj poles at Rootz Gallery

The bisj poles at Rootz Gallery

Originally the poles were left in the woods after the bisj festival where they were returned to the earth. Just after World War II, however, missionaries and museums began collecting the poles.[8] Rootz Gallery has had six bisj poles in its collection, two of which currently remain. They are both from the collection of Mr. Fons Schobbers. Fons Schobbers made the trip from the Netherlands to Papua in the 1990s with a large ship. He had a fascination with the Asmat and their cultural heritage. From the ship he sailed with smaller boats into the area of the Asmat and purchased a large quantity of items in good consultation with the Asmat and at a fair price.

Below is a description of the bisj poles currently held by Rootz Gallery.

The figures face each other.

Bisj pole 4,5 meters

You can see eight figures facing each other. In the tsjémen hornbills can be seen. This is a reference to headhunting, because hornbills often have a red beak from the red fruits they eat. This looks like blood. The curly motifs refer to the curly tail of couscous (fatshep, marsupials that also eat fruit). White pigment (powdered lime) and black pigment (charcoal) were applied to the bisj pole. The lime also acted as protection against pests. There is ochre pigment in the cutouts in the wood. The figures have earrings in of sago palm fiber (raffia).

€3500

The figures face the front.

Close-up of the tsjémen.

Bisj pole 3 meters

Bisj pole 3 meters

Five figures on top of each other are all facing one side (wherever the “flag” or tsjémen is located). These figures also have cutouts on their bodies in which there is no pigment. The motifs in the tsjémen probably refer to the praying mantis (wenet).

€2500

You can also find bisj poles mostly in museums, such as the Wereldmuseum Amsterdam (formerly Tropenmuseum) and even in the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

Suggested reading

- Rockefeller, Michael Clark. The Asmat of New Guinea: The Journal of Michael Clark Rockefeller, edited by Adrianus Alexander Gerbrands. New York: Museum of Primitive Art, 1967.

- Kuruwaip, Abraham. “The Asmat Bis Pole: Its Background and Meaning.” In An Asmat Sketch Book, edited by Frank A. Trenkenschuh. Vol. vol. 4. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1974, pp. 5–32, 8–9, 10, 11, 18, 19, 20.

- Konrad, Gunter, Ursula Konrad, and Tobias Schneebaum. Asmat: Life with the Ancestors: Stone Age Woodcarvers in our Time. Glashütten: F. Brückner, 1981.

- Schneebaum, Tobias. Asmat Images from the Collection of the Asmat Museum of Culture and Progress. Agats, Indonesia: Asmat Museum of Culture and Progress, Agats, Papua Province, 1985.

- Schneebaum, Tobias. Embodied Spirits: Ritual Carvings of the Asmat. Salem, Mass.: Peabody Museum of Salem, 1990, p. 70.

- Smidt, Dirk A.M., ed. Asmat Art: Woodcarvings of Southwest New Guinea. Leiden: Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde, 1993.

- Konrad, Gunter, and Ursula Konrad, eds. Asmat: Myth and Ritual: The Inspiration of Art. Venice: Erizzo Editrice, 1996.

____________

[1] A book about this specific topic: Adrian A. Gerbrands, Wow-Ipits: Eight Asmat Woodcarvers of New Guinea (Den Haag: Mouton and Co., 1967).

[2] Pauline van der Zee, Bisj-palen: Een woud van magische beelden, (Amsterdam: KIT Publishers, 2007), 21.

[3] Tobias Schneebaum, Asmat Images: From the Collection of the Asmat Museum

of Culture and Progress (Agats: Asmat Museum of Culture and Progress, 1985), 9.

[4] Ibid., 33.

[5] Pauline van der Zee, Bisj-palen: Een woud van magische beelden, (Amsterdam: KIT Publishers, 2007), 17.

[6] Pauline van der Zee, Bisj-palen: Een woud van magische beelden, (Amsterdam: KIT Publishers, 2007), 18.

[7] Metropolitan Museum, “Bis Pole,“ https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/313830.

[8] Dirk A.M. Smidt, Asmat Art: Woodcarvings of Southwest New Guinea (Clarendon, Vermond (VS): Tuttle Publishing, 2012), 24.